1 Introduction

Describing a ’set of abilities around the use of data as part of everyday thinking and reasoning for solving real-world problems’ [1], data literacy is key for an increasingly digital and data driven society [2]. Along with the ability to solve real-world problems with the use of data, the critical reflection with data is becoming increasingly important [3]. Moreover, there are many risks of incorrect assumptions based on data that might lead to incorrect knowledge and decisions. This then might further fuels biases in societies. There is a responsibility for those communicating through data to inadvertently reduce biases [1].

Ethics is a moral philosophy that aims to systematize, defend, and recommend concepts of right and wrong behavior and action [4] [5]. This often results in extensive discussions of complex, interdisciplinary and ambiguous questions – especially in an increasing dynamic and complex global society. To become agent in their decision making, ethical guidelines based on democratic values had been introduced in different literacies such as media literacy [6] and AI literacy [7]. As the relevance of data increased along with the difficulty for human beings to comprehend the influence on our knowledge and decision-making, ethics need to be further considered in the data literacy frameworks.

Ethical considerations should not be understood as a side subject to be taught with many others, Ethical questions in data literacy are a core element and basis for all subsequent decision making. Especially competencies that consider critical thinking and enabling agency are barely mentioned in current data literacy frameworks. As the relevance of data increased along with the difficulty for human beings to comprehend and process, the influence to our knowledge culture should be further considered in the frameworks.

While there are already concepts on teaching ethics in data literacy [8]. However, when training ethics in data literacy those examples are less from actual daily work but from social media interaction [9]. To prepare future workforce for ethical decision making through data, the examples given should be realistic and actual examples that professionals working with data experience.

Indeed, many literacy discussions consider ethical discussions as important for supporting empowered citizens [10] [6] [9]. Still, when applying ethics in the curricular topics of data literacy, they are often pushed to the side in favour of more applicable topics such as data visualisation, data analytic or data tasting. The objective of this contribution is to invite data scientist and mechanical engineers to reflect on ethical question in their work with data and collect those questions into actual ethical question that arise in daily business. The research question is therefore:

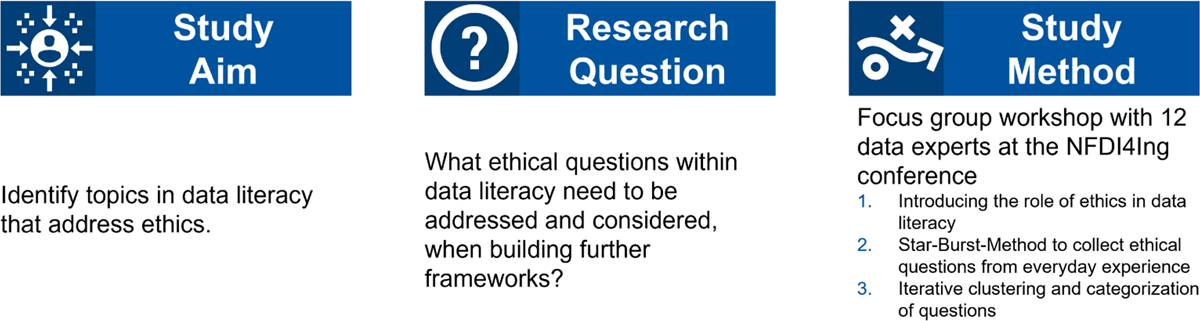

What ethical questions are present with data experts and should therefore be addressed and considered as examples, when applying data literacy frameworks?

The first part of this contribution will highlight ethics concepts in existing data literacy frameworks. The following part will introduce a focus group study as a explorative method to collect ethical issues in the interaction with data. The focus group study took place among data literacy experts at the NFDI4Ing conference in November 2022. The different ethical questions are summarized to identify key ethical categories that should to be included in ethics discussions on data literacy. Finally, the conclusion will open further potential research questions in data literacy and give examples for addressing ethical questions in daily practice with data.

2 The role of ethics in data literacy frameworks

Contrary to its importance in decision making, ethics remain a minor course within data literacy. They rarely play the central role that is required. Most of the current frameworks that do consider data ethics as important then lack concrete applicable topics in their curricula. They rarely are concrete and give hints to educators on how exactly they can apply ethics in data literacy programs.

For example, Heidrich et al. introduce ethics as a side competency in their framework [11]. In the study from Wolff et al., they identify through card sorting that professionals see ethical competence as highly relevant within data literacy, but do not give further examples on what asked professionals understand by this [1]. Card sorting is a user research technique used to help evaluate the information by having participants organize topics into categories that make sense to them. In Grillenberges and Romeikes approach to create a data literacy Competency Model based of Risdale et al., they introduce their competencies along the data management cylce and divide them into process and content-oriented competencies [12]. They introduce a layer called ethics, but do not connect it visibly with the introduced competencies or exemplify it. Schüller et al. introduce a comprehensive data literacy framework considering both comprehensive and selective competencies along a data value chain [10]. In their model ethics is pushed to the side of the framework and is seen as a separate ethics literacy.

A general guideline for data processing can be understood in the FAIR principles that emphasize the importance of making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [13]. The FAIR principles were introduced by the FORCE11 community and function as a framework to ensure that scientific data is managed in a way that maximizes its utility and impact (FAIR) [14]. They were introduced by and function as essential criteria for data stewardship, aiming to enhance the ability of machines to automatically find and use data, in addition to supporting its reuse by individuals.[14] However, implementing these principles can be challenging due to the diverse and complex nature of data and metadata standards across different disciplines, requiring significant effort in data curation and management to fully achieve FAIR compliance.

Closest to concrete examples in ethics is the research team around Giese. They introduce ethics as part of the transparency and awareness pillar [9]. This pillar is one of three other pillars and additionally includes a law and technical component. The ethical pillar in the concept of Giese et al. was introduced through real-world examples and thinking and pairing exercises [9].

In their example, they introduce a case from twitter, which indicates the importance of (social) media understanding, when it comes to ethics in data literacy. The example of Giese’s application of ethics reveals that ethics within data literacy is often connected to other literacy types. This might be the reason why Schüller et al.frameworks introduce ethics as an additional literacy in their concept.

Ethical considerations in data literacy should be seen as a core element for all subsequent decision making. They should not merely be applied at some point in the process, but always remain in the core of a data literacy concept. Regardless of the data processing step aside from the how there should always also be the question of the why. As ethical questions require the consideration of a wide range of stakeholders and other fields, therefore ethical questions are usually overlapping with other literacy concepts.

3 Method focus group study

To answer the research question concerning the content of the ethic topics, a focus group study with data literacy experts and professionals was conducted. Focus group studies are a qualitative discourse method in which a group is stimulated to discuss a specific topic [15]. While the researchers provide a specific focus, such as ethics in data processing, the data is collected through the observation of a groups response through this topics. According to Kitzinger, this method is used to generate and explore questions among a group and encourage the development of their own analysis of common experiences [16]. While this method might not give a deep insight into individual perspectives and experiences [15], it is well suited to identify norms and values based on a common experience within a group [16].

Therefore, this method has been selected to gain a further understanding of ethical issues among a group of data experts (see figure 1). Due to being a complex topic, ethical problems are a helpful to identify shared experiences in the decision making process of data. Through the discussion in groups, the individuals might find solutions or at least see that there are patterns to their experienced dilemma. This is helpful for developing a collection of applied ethic topics that go beyond the usual questions of data privacy.

The focus group study was conducted at the NFDI4Ing conference in October 2022 to a group of 15 participants with various background in mechanical engineering, information science and software engineering. After defining ethics and their relation to data literacy, the starburst method was introduced to collect ethical questions from the experts in smaller rotating groups.

The star bursting method is a method in design thinking to collect questions in order to understand a problem from different perspectives [17]. In this method a star with six spikes represents six question words (how, who, why, what, when and where). The task for the participants is to reflect and fill the question words with ethical questions they have faced in their professional work with data.

The group was divided into two groups and asked to collect and discuss ethical question based on the six question words. The idea behind the ethical questions was not focused on finding solutions at this point, as it is the nature of such questions to not be easily answerable from the point of one domain. Rather, this collection was useful in understanding the spectrum of ethical questions and the contexts that need to be considered when working with data. These questions were subsequently anonymized and categorized and are presented in the following part.

The categorization of the questions was conducted with an iterative open coding method following the grounded theory method. The grounded theory is a research method and approach towards data for generating theories of medium range [18]. While the application of grounded theory would have exceeded the analysis of the focus groups study, the iterative proceeding of summarizing, coding and categorizing to identify a core image was implemented [18].

3.1 Results of the focus group study – categorizing data ethics

Through this study around 20 ethical questions in data focused research were collected among the experts. While the explicit answering of these questions was not the aim of the study, the different considerations help to gain an understanding of ethical aspects that need to be considered when addressing ethical questions in data literacy.

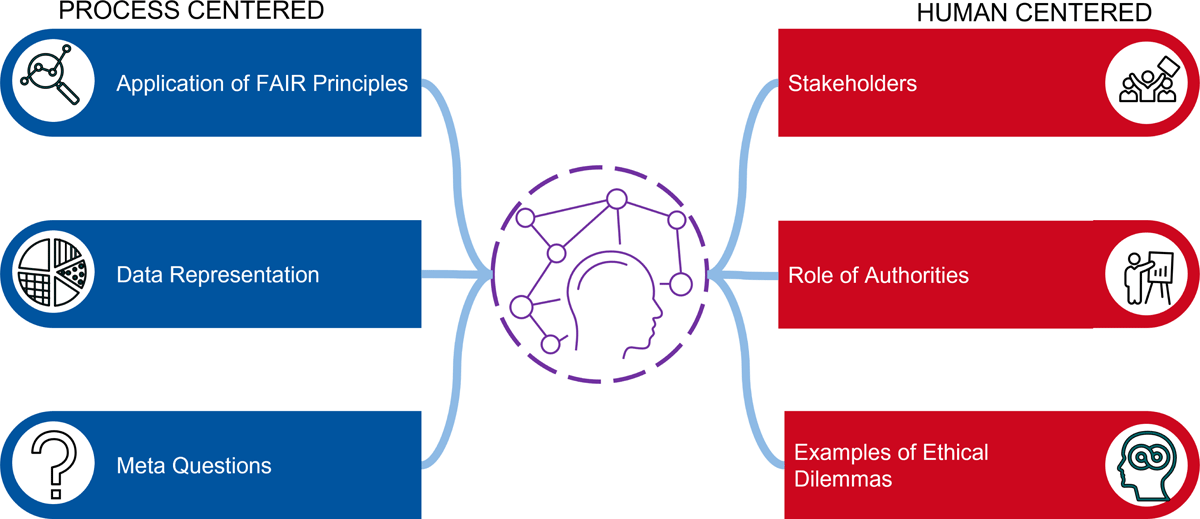

The ethical questions were summarized in the following six categories (See figure 2): the application of the FAIR Principles (4), Stakeholders (4), Role of Authorities (3), Data Representation (3), ethical problems and Examples (3), and a category consisting of questions that did not fit the other categories (2).

The clustering of the categories in human oriented and process oriented describes whether the questions address data interaction processes or reflect context in which data is processes. Process oriented are ethical question that address the interactions with data along a data management process of gathering, analyzing, visualization and documentation. Human centered questions are addressing different stakeholders interacting with or through the results and decision-making through data.

The FAIR principles are findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) [14]. An example question based on these principles was ‘When should data transparency be given and when is it too much?’. As transparency is an underlying theme and the central aim of the FAIR principles, this question addresses an important decision that people working with data are considered daily.

The Stakeholder category reflects different groups that are affected by data-based applications. The question pair reflecting this is ‘Who might struggle with such ethical standards?’ and ‘Who would mainly benefit from such ethical standards?’. This category has an overlap with both the role of authorities and data representation categories.

The role of authorities has evolved around the power that states and companies hold. An example question here was, ‘Where can I turn to with an ethical problem in data?’ in combination with ‘Who could have the responsibility for deploying ethical standards in different application areas (e.g. research, practice)?’. This is more of a meta-category describing the organization of ethics rather than their application, which is reflected more in the Stakeholder category. It might be a subcategory of the Stakeholder category but is presented here as a separate category due to the amount of questions that arise in the discussion.

Data Representation overlaps with Stakeholders and includes questions like ‘What can we do against misinterpretation of data?’ and ‘How can we show that data representation reflects the truth?’. This category is strongly connected to practical guidelines in design and visualization. As the visualization of data is closely connected to visual and media literacy, those ideas might be found in overlapping areas of the other literacies.

The ethical problems and Examples category collected questions from concrete, applied examples in daily life. An example question for the category is ‘How can we detect bias in data?’. The further collection of examples would be helpful for a concrete design of an educational curriculum, as this category tends to become more specific than the others.

There were further ethical questions that were sorted into the remaining collected category, such as ‘When should data literacy and ethical maturity be taught?’, which is more oriented towards education, and ‘How could Ethics impede data content generation?’ as further practical ethics questions. As this is a first attempt to address the variety of ethical questions in data management, further focus studies might develop further categories based on those questions.

Finally, in a reflection and feedback round of the study, the exchange gave new insights for the group as well as for the data. The biggest downside addressed by the group was that this exchange was too short and could have been extended further. Still, the collected categories extend current ethics in data literacy with a collection of topics that professionals recently face.

For the design of educational frameworks this suggests that ethics in data literacy is both human centered and process oriented. Ethics is present through the full data management cycle. Along with the known FAIR Principles the perspective of different stakeholders and identification of authorities in ethical problems are relevant to teach about data ethics. Also the question about the limitations of representing and suggesting truths in your own data set are suitable reflecting questions. Further applications of those results need to be tested further.

4 Conclusion and outlook

This paper aims to broaden the understanding of data literacy by including discussions and critiques from media literacy into the development of a data literacy framework. This approach, with a literature review on how ethics is applied in combination with a focus group study among data literacy experts, can be seen as a first step towards developing ethical foundations in literacy frameworks that go beyond data privacy discussions.

In order to adress the research questions:

What ethical questions are present with data experts and should therefore be addressed and considered as examples, when applying data literacy frameworks?

First a literature study compared how different data literacy concepts applied ethics in their frameworks. As a result, it became clear that ethics is often seen as important but is rarely prominently applied. Additionally, it was concluded that applied reflection of ethical questions needs to include multiple perspectives. Still, the shift of ethics into the center is required, as ethical considerations are not limited to one scientific field.

To fill ethics in data literacy, a focus group study was conducted among data literacy experts at the NFDI4Ing conference in October 2022. Through an online workshop around 20 ethical questions were collected, categorized, and introduces (see figure 1). The main categories are the Application of FAIR Principles, Stakeholders, Role of Authorities, Data Representation, ethical problems and Examples (see figure 2). These questions give further insights into themes that ethical programs in Data literacy apply and which are worth further examination.

As a next step, the scientific exchange between different literacy framework is highly recommended. Some of the collected ethical questions overlap other scientific fields such as media or sustainability literacy. Through further interdisciplinary exchange, data literacy will empower professionals, students and educators to make informed data-based decisions. First steps in this direction have already been achieved in feburary 2024 by an Ethics Working Group of the ELSA-section in the NFDI [19]. They had been established to ensure that ethical considerations are integrated into every aspect of research data practices and aim at addressing the complex ethical issues associated with research data management.

5 Annex – Table

Table 1: Table showing how questions are defined and categorized

| Category | Definition | Questions |

| Application of FAIR Principles | Questions that are related to the FAIR Principles in either pointing towards an answer or giving guidelines for those questions. The FAIR Principles are findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR). | - How can I discern how long my research data must remain in the area of confidentiality until we have safeguarded the internal scientific process of gaining knowledge? - Where should data be stored? Is only EU really applicable? - When should data transparency be given and when is it too much? - Who would have the responsibility for the implementation of FAIR principles? |

| Data Representation | Data Representation describe questions that evolve around rules for visualizing and representing data without misleading implications. | - Why should ethical aspects influence data visibility? - What can we do against misinterpretation of data? - How can we visualize the truth (data visualization)? |

| Meta Questions | This category collects questions that are discussing the (teaching) methods behind ethics in data literacy. | - How could ethics impede data content generation? - How can we distinguish between ethical methods and ethical data content? - When should data literacy and ethical maturity be taught? – is this a topic that needs to be started in primary school and WHEN should the levels be deepened? |

| Examples of ethical problems | The ethical problems and Examples category collected questions from concrete, applied examples in daily life. | - How can we detect bias in data? - How have ethical considerations evolved over time and how do we address research subjects that are no longer up to date from an ethical point of view? - What are good examples for ethical questions in data literacy? - Where can I turn to with an ethical problem? |

| Stakeholders | The Stakeholder category reflects different groups that are affected by data-based applications. | Who would be mainly affected by such ethical standards? - Who might struggle with such ethical standards? - Who would mainly benefit from such ethical standards? - Who are the stakeholders and what requirements do they have? |

| Role of Authorities | The role of authorities evolves reflections on entities that give authority in ethical questions. | Who is the authority for ethical standards? - Where can I turn to with an ethical problem? - Who could have the responsibility for deploying ethical standards in different application areas (e.g. research, practice)? |

Data Availability

Data was not created through the work on this paper

Software Availability

Software was not created through the work on this paper

6 Acknowledgements

This paper would not be possible without opportunity to conduct a workshop at the NIDI4Ing conference 2022. The authors thank the participants of the workshop for their active and engaged contribution to the ethical questions, insights in the ethical dilemmas they have faced in their professional life and the open exchange on eye-level.

7 Roles and contributions

Samira Khodaei: Conceptualization, Execution, Writing, Original Draft

Anas Abdelrazeq: Review & Editing

Ingrid Isenhardt: Review & Editing

References

[1] A. Wolff, D. Gooch, J. J. Cavero Montaner, U. Rashid, and G. Kortuem, “Creating an understanding of data literacy for a data-driven society,” The Journal of Community Informatics, vol. 12, no. 3, 2016, ISSN: 1712-4441. DOI: http://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v12i3.3275.

[2] D. Taibi, L. Fernandez-Sanz, V. Pospelova, et al., “Developing data literacy competences at university: The experience of the dedalus project,” in 2021 1st Conference on Online Teaching for Mobile Education (OT4ME), IEEE, 2021, pp. 112–113, ISBN: 978-1-6654-2814-9. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1109/OT4ME53559.2021.9638912.

[3] B. Motyl, G. Baronio, S. Uberti, D. Speranza, and S. Filippi, “How will change the future engineers’ skills in the industry 4.0 framework? a questionnaire survey,” Procedia Manufacturing, vol. 11, pp. 1501–1509, 2017, ISSN: 23519789. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2017.07.282.

[4] J. Baggini and P. S. Fosl, The ethics toolkit: A compendium of ethical concepts and methods, [Nachdr.] Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2010, ISBN: 1405132302.

[5] J. Ferretti, Daedlow K., J. Kopfmüller, M. Winkelmann, A. Podhora, and Walz, R., Bertling, Reflexionsrahmen für forschen in gesellschaftlicher verantwortung, Berlin, 2016.

[6] M. Leaning, Media and information literacy: An integrated approach for the 21st century (Chandos information professional series). Cambridge, MA and Kidlington: Chandos Publishing an imprint of Elsevier, 2017, ISBN: 9780081002353. [Online]. Available: https://aml.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/JMLVo.64No.12-2017.pdf.

[7] D. T. K. Ng, J. K. L. Leung, K. W. S. Chu, and M. S. Qiao, “Ai literacy: Definition, teaching, evaluation and ethical issues,” Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 504–509, 2021, ISSN: 2373-9231. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.487.

[8] Shannon Vallor and William J. Rewak, An Introduction to Data Ethics. 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.scu.edu/media/ethics-center/technology-ethics/IntroToDataEthics.pdf.

[9] T. G. Giese, M. Wende, S. Bulut, and R. Anderl, “Introduction of data literacy in the undergraduate engineering curriculum,” in 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), IEEE, 2020. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1109/educon45650.2020.9125212.

[10] K. Schüller, “Ein framework für data literacy,” AStA Wirtschafts- und Sozialstatistisches Archiv, vol. 13, no. 3-4, pp. 297–317, 2019, ISSN: 1863-8163. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11943-019-00261-9.

[11] J. Heidrich, P. Bauer, and D. Krupka, “Future skills: Ansätze zur vermittlung von data literacy in der hochschulbildung,” Hochschulforum Digitalisierung, no. 37, 2018.

[12] A. Grillenberger and R. Romeike, “Developing a theoretically founded data literacy competency model,” in Proceedings of the 13th Workshop in Primary and Secondary Computing Education, New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2018. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1145/3265757.3265766.

[13] Force11, Guiding principles for findable, accessible, interoperable and re-usable data publishing version b1.0 – force11, The Future of Research Communications and e-Scholarship, Ed., online, 5.06.2024. [Online]. Available: https://force11.org/info/guidingprinciples-for-findable-accessible-interoperable-and-re-usable-data-publishing-version-b1-0/.

[14] European Commission, A european strategy for data: Com(2020) 66 final, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0066&from=EN (visited on 12/07/2022).

[15] M. Schulz, “Quick and easy!? fokusgruppen in der angewandten sozialwissenschaft,” in Fokusgruppen in der empirischen Sozialwissenschaft, M. Schulz, B. Mack, and O. Renn, Eds., Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2012, pp. 9–22, ISBN: 978-3-531-19396-0.

[16] Jenny Kitzinger, “Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups,” BMJ, vol. 311, no. 7000, pp. 299–302, 1995, ISSN: 1468-5833. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [Online]. Available: https://www.bmj.com/content/311/7000/299.

[17] S. Blakely, Starbursting technique: How to brainstorm using starbursting, masterclass.com, Ed., 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/starbursting (visited on 12/07/2022).

[18] F. Breuer, P. Muckel, and B. Dieris, Reflexive Grounded Theory: Eine Einführung für die Forschungspraxis (Springer eBook Collection), 4. Aufl. 2019. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 2019, ISBN: 9783658222185. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-22219-2. [Online]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-22219-2.

[19] NDFI.de, Ethik workshop februar 2024|nfdi, 21.05.2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nfdi.de/tf-ethik-workshop-februar-2024/.